You’ve reached your limit!

To continue enjoying Utility Week Innovate, brought to you in association with Utility Week Live or gain unlimited Utility Week site access choose the option that applies to you below:

Register to access Utility Week Innovate

- Get the latest insight on frontline business challenges

- Receive specialist sector newsletters to keep you informed

- Access our Utility Week Innovate content for free

- Join us in bringing collaborative innovation to life at Utility Week Live

Network operators need to make big changes to transition to ‘DSOs’ if we are to meet decarbonisation targets. But how much progress are they actually making? Elaine Knutt investigates.

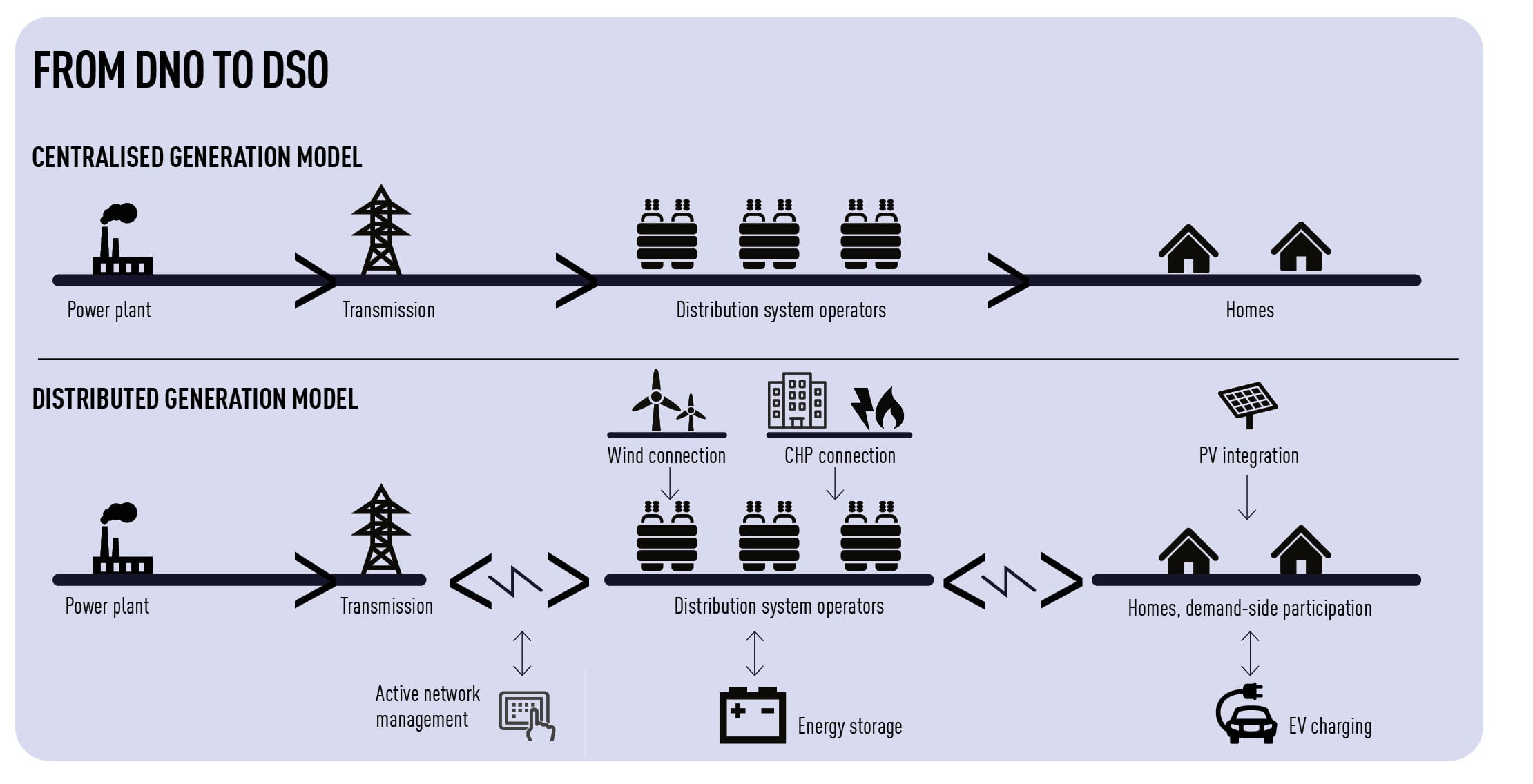

The Ofgem-regulated distribution network operators (DNOs) are on a journey towards becoming distribution system operators (DSOs), with a minor change in terminology hiding a vast change in the scope of their responsibilities.

The Ofgem-regulated distribution network operators (DNOs) are on a journey towards becoming distribution system operators (DSOs), with a minor change in terminology hiding a vast change in the scope of their responsibilities.

As DSOs, it’s expected that they will coordinate and balance regional grids; maintain and manage new connections; procure demand-side management flexibility, including at the grid edge; create new markets with maximum participation from innovators and community groups; capture, process and share network data while maintaining cyber-security – and all within a profit-limiting, cost-sharing regulatory environment that Ofgem has yet to spell out.

But while there’s general agreement about the nature and scope of the transition, there is still some uncertainty about the definitions, milestones and timescales. As independent energy consultant John Scott sums up: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen clearly described what a DSO actually is intended to be. There is plenty of PowerPoint-level material, but it’s incredibly vague and generalised.”

At the Association for Renewable Energy and Clean Technology (REA), which represents many of the low carbon generators that will operate in this new territory, head of policy Frank Gordon is also in the dark: “What exactly is a DSO? If we knew, we could track the requirements, but it’s not finalised as of yet. No-one knows exactly what it means, the Energy Networks Association [ENA] and the networks have their ‘road maps’, and there are various consultations on what it might look like, but it’s still quite ambiguous as to how it turns out.”

The ENA-brokered Open Networks Project, active since 2017 and drawing in representation from the DNOs, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), Ofgem, academics and trade bodies, aims to clarify objectives for the transition, and facilitate the collaboration necessary to achieve them. As part of its consultation on its programme for the coming year, it recently announced that it would publish a “DSO Implementation Plan” by summer 2020 – a document that will no doubt help to fill in gaps in the sector’s knowledge.

The ENA also highlighted the progress it had made in 2019, where it published its commitment to exploring the markets to procure flexibility; a “system resource register”, a web page giving access to the six DNOs’ published data on their distributed energy resources; and guidance on how the DNOs would collectively manage connection queue management.

The DNOs themselves express confidence in the process. At Electricity North West, regulation and communications director Paul Bircham says: “We’ve got a clear sense of direction overall, so the steps we need to take are pretty clear. What’s really helped us make progress is having all the DNO, National Grid and other stakeholders working together through the Open Networks Project to scope out functions, especially where we are engaging with other markets and can seek standardisation. I think we’re quite aligned [with the other DNOs], we’re making progress, and we also have a sense of alignment with Ofgem.”

Nevertheless, there are perceptions in some quarters that the transition process, and the stewardship of the Open Networks Project, has lacked momentum. “There have been lots of good noises around the transition, but we echo what Ofgem said in its open letter to the ENA [in July 2019]. It talked about a lack of clarity on timelines and the need for tangible objectives,” says Conor Maher-McWilliams, head of flexibility at Ovo-owned Kaluza. “It needs to create concrete, tangible objectives against which success can be measured. There have been delays and no clear finish line.”

Scott fears that, in the absence of clearer guidance from the Open Networks Project and Ofgem, DNOs’ boards and shareholders may be steering in the right direction, but not hitting the accelerator. “Are the investors saying to the chief executives, ‘OK do your part, do some trials, but until Ofgem shows broadly the direction it wants to see, don’t go too far?’” Scott suggests. “Ofgem needs to indicate what it means by the DSO role, and how DSOs will earn their revenue.”

At Smarter Grid Solutions, whose Distributed Energy Resource Management Software (DERMS) is currently used by four UK DNOs, executive director Graham Ault shares a similar view. “A year or two ago, there was lots of thinking and ideas; now people are trying to work out what’s genuinely valuable and achievable and how it will slot into the RIIO-ED2 price control framework. But I wonder if the DNOs are thinking, ‘what bit of the DSO agenda shall we invest in now?’. [Without clarity from Ofgem] it’s a bit chicken and egg.”

Nevertheless, as he points out, the transition is making itself felt on the DNOs’ corporate structures. “Many of our contact points in the DNOs have picked up new and huge responsibilities, such as head of flexibility, and they’re actively recruiting their teams. It’s an area of great interest and relevance, it’s great to work with our customers and there’s all to play for, for us and the whole industry.”

Progress at Northern Powergrid

With no universally agreed definition of a DSO, the DNOs are free to define their own. At Northern Powergrid, head of regulation and strategy Jim Cardwell identifies three key parameters: managing a more complex connection landscape and acting as a catalyst for decarbonisation; interfacing more effectively with the electricity system operator (ESO) and sharing data that allows Northern Powergrid full visibility of what’s on its network; and creating a “universal service offering”, or consistency in connection processes across its operations and those of other DSOs.

Against these criteria, Cardwell is confident that Northern Powergrid is making good progress. “We’d say we think we’re already behaving like a DSO – only one organisation has operational responsibility for the grid in Yorkshire and the North East, and that’s us. Increasingly, our focus is on flexibility and an active grid, which is synonymous with a DSO. We’re actively managing distributed energy resources, not passively. I’m not sure there’s a point you pass when you say yesterday we weren’t but now we are, but we feel we are now acting as a DSO.”

In terms of the ESO interface, Cardwell says that it needed to “have visibility on contracts between generators and National Grid ESO in our territory. We will share data between networks, so that we can see what it does to the system – we don’t want to pull in different directions.”

Northern Powergrid has previously pointed out that the scale of distributed generation on its network – at 3.3 GW – means its contribution to the national grid is greater than Hinkley Point C’s will be.

At Western Power Distribution, DSO and future networks manager Nigel Turvey can also list the company’s achievements. “We are well down a path in terms of what we are trying to achieve. We pushed out our DSO strategy which describes the general direction, and we got it about right – we have more visibility in our control of the network, we’re using third parties for flexibility. We’ve made significant advances in the past 18 months in terms of flexibility procurement. It’s a continuous process, but I think we’re a long way down the road.”

He also describes sharing data with the ESO to facilitate full visibility, and therefore control, of its network.

“To an extent it is an issue, and we have worked with the ESO on it. For instance we ran a pilot in the South West jointly with the ESO looking at issues around visibility. So we are building links between our systems, so that both sides get visibility. Historically, we haven’t needed to do this, but as we get more generation on the networks, there is more need for this data.”

Open data needed

Whatever shape the DSOs eventually take on, they will need to provide the data to support the new energy landscape, to manage and balance the grid, but also to provide “open data” that allows third party entrepreneurs to access the energy market. That could involve real-time readouts of consumption data and headroom at substations, or carbon intensity. They will also need to provide the physical trading platform for peer-to-peer local trading in the energy market.

In July, Ofgem’s open letter to the ENA specifically said that the DNOs needed to improve operational monitoring data and communications infrastructure. The Energy Data Taskforce report, published in the same month, also called for a significant shift in the DNOs’ and ESO’s attitude to data, with a presumption that it should be “discoverable, searchable, understandable”, and use standardised data structures and interfaces.

In December 2019, in a move timed to coincide with the submission of RIIO2 business plans by gas network operators and the ESO, all the DNOs published their outline digitalisation strategies discussing their progress towards the taskforce’s goals.

At Smarter Grid Solutions, however, Ault says some of its DNO customers are already fully exploiting its DERMS software to manage generation, flexibility, storage and even the interface with EV charging operators, but acknowledges that stepping up further on data accessibility could be a challenge. “The DSOs will also need big, generalised data platforms. Data will create challenges for DNOs – they will want to be cyber-secure, and maintain commercial confidentiality.”

At Northern Powergrid, Cardwell says the company is making headway: “We have increased our work on data and digitalisation; we see that as an underpinning technology enabler. We have invested, hired new staff and reallocated staff.

“At the moment, we are looking at the art of the possible. Some of our data is quite old school, it’s in spreadsheets and tables – we want to take it forward to an open data environment, and expect that to happen collaboratively across DSOs to achieve common approaches.”

At flexibility provider Kaluza, however, Maher-McWilliams fears that much of the data that will unlock innovation in networks simply doesn’t exist.

“They are making existing data sets more accessible and their network needs more transparency, but in key areas we just don’t have the network data required to develop a truly smart grid. This is particularly true at lower voltages and the DNOs need to invest in more network monitoring software.”

In general, Maher-McWilliams sees progress as frustratingly slow: “There are some early stage pilots, and some DNOs are investing, but the scope is so small at the moment. The scale of the upgrade – and the fact that data is certain to be a vital part of the future DSO role – means it is something they should be investing in now, even in the absence of other certainties.”

In ENW’s patch, Bircham describes how it is investing in new £20 million network management system (NMS) software, delivered in partnership with Schneider Electric, and due to go live later this year. The system will give ENW full real-time data on network loading and capacity, and also generate the data sets that can be shared with external providers.

“It’s a next generation NMS, specifically designed to support our activities as a DSO,” Bircham says. “As we move to a world with more generation and more flexible demand-side response, that real-time understanding will be essential. We anticipate that all the DNOs will need this kind of step-change in RIIO-ED2”.

Flex auctions

All of the DNOs have also adopted one of the clearest signs of transition: flexibility auctions. By setting up tender processes for storage or generating capacity in locations with network constraints, the DNO can defer capital investment – while being compensated by financial allowances from Ofgem. In doing so, they are creating routes to market for a range of new players: community energy projects, the aggregators of new-style “prosumers” or EV charge point operators.

At WPD, Turvey was speaking shortly after the company launched the largest auction yet, at 334MW. He acknowledges there is more to do, but feels that its “Flexible Power” brand is on track.

“In our most recent tender, we had more participants looking to apply, so there is more confidence in the marketplace. But it’s important to come up with a product that is simple to understand, has simple terms and liabilities, and is predictable – all these things help to build confidence in a long-term market.”

However, at the REA, Gordon says the fanfare over the first auctions shouldn’t disguise the fact that they represent a fraction of the scale needed.

“We’d like to see the DNOs do more to become an enabler of the low carbon energy system. The auctions are at too small a scale to stimulate the market – they’re still pilots, there isn’t even a recurring programme in place. They should be an order of magnitude higher, for network stability.”

In evidence, he points to the big blackout in August last year when a lightning strike tripped a lot of generation plant off the system. “A lot of capacity came offline, but energy storage came on to prop up the system; 500 MW helped to soften the blow of the blackout.”

Flex providers themselves fear the auctions offer neither the scale nor the contractual terms they need.

At the larger end of the scale, LimeJump offers aggregated capacity from a network of industrial and commercial clients, selling mainly to National Grid’s Balancing Mechanism. So far, it has just one signed contract in place with a DNO. Its chief executive, Erik Nygard, argues that the size of the market just isn’t large enough to justify acquiring capacity at the smaller DNO scale.

“There is not enough market size, they’re kind of dabbling and testing. It is only worthwhile for us to take part when we have customer assets that are contracted to do other stuff [on the wholesale markets or Balancing Mechanism]. If there’s a DNO tender, I don’t want to acquire customers, because I couldn’t make the cost of the acquisition work against the size of the opportunity.”

Speaking hypothetically, he says “If the whole market is 50 to 100MW, and there’s maybe five to ten companies chasing it, even if I’m lucky I only get 20 per cent. The economics are not quite there yet.”

Operating at the residential level is Kaluza, which has just announced it is providing WPD’s live market with additional capacity from a portfolio of 20 domestic batteries installed in Lincolnshire homes. But Maher-McWilliams feels that many of the auctions so far have been structured to favour industrial customers and large aggregators, not the “grid edge” residential devices.

“The focus should be on maximising participation, but current procurement focuses on long-term commitments over a number of months. For us to meet those expectations, we have to build substantial headroom into the bidding process – the amount of flexibility available from heating systems, for example, varies with weather and is much more predictable over shorter time scales,” he says.

He notes that WPD’s ability to forecast and assess requirements in its Flexible Power market on a weekly basis is the best available offer. “The market hasn’t been designed with flexibility in mind. We are actively engaging with the DNOs; they recognise this is a step we need, but we want to see it happening as quickly as possible.”

Over at ENW, Bircham offers a different take, saying that – in his experience – flex providers haven’t offered a price point that undercuts traditional investment in cables and transformers. “We’ve gone to market, but we haven’t signed any contracts that involve new connections. The offers have been too expensive, and alternative steps are more efficient.

“We explicitly checked in with Ofgem over this, asking ‘what’s your view, should we pay a premium price in order to stimulate the market?’ And their view was very clear, it would be wrong in principle to pay an inefficient price compared to alternative actions.”

Bircham agrees, though, that increased standardisation will be necessary to drive expansion in the flexibility market, by helping providers to structure offers. “The Open Networks Project has been helpful in facilitating this, and moving to a standardised product set. This year, there will be a set of definitions of products that DSOs need to buy from the market. So wherever you go, you can understand what the product definition is.”

In the dark

At the moment, the DNOs are in the early stages of writing business plans to be submitted to Ofgem ahead of the RIIO2 price control period. But, as Northern Powergrid has pointed out, they are business planning without a “baseline” understanding of what a DSO actually is, and how Ofgem will incentivise flexibility and decarbonisation. DNOs’ role is shifting from “fit-and-forget” to active network management, and their assets are not so much new physical infrastructure as software systems or ability to share network data and price signals, but it’s not known how the price controls framework will reflect that.

Meanwhile, decarbonisation is now an urgent goal, and the DSOs are widely envisaged as a key enabler in decarbonising the energy system. Nevertheless, today’s regulatory environment dictates they act in a technology-agnostic way, treating high carbon-intensive diesel generation the same way as biomass and solar or wind.

At the REA, Gordon says: “In the past, the rules by which the DNOs operated created a straight blocker to renewables, and that needs to change. There could be very high connection costs in some parts of the country, which was partly a product of the RIIO-ED1 framework, so we need new ways of looking at it.”

Flexibility needed now

Cardwell also wants to know how Ofgem will view other factors. “What societal and environmental factors can be factored into our decision-making process? There’s also a social and environmental value to electrical losses; are we allowed to factor that in [to investment planning]? At the moment, we don’t distinguish between different forms of generation.”

So far, Ofgem has incentivised the procurement of flexibility on the grounds that it is more cost-effective than adding network capacity. While the expectation is that this will continue in RIIO-ED2, no details have yet been published. As Scott says: “We would expect the DSOs to make a reasonable return from flexibility. It clearly has a cost, and as it grows DSOs will need to invest to deliver their digitalisation strategies. At present we don’t know how they will be remunerated for their services and what rewards and penalties might apply.”

He points out that there is an inherent contradiction between traditional cables-and-transformers companies and the fleet-footed, digitally enabled entities evoked by all the PowerPoint slides.

“[Flexibility] is what Ofgem wants to hear, but the way these companies currently earn their money is by installing cables and substations. These are commercial entities with investors to satisfy. These investors aren’t looking for fantastic entrepreneurialism – they typically want steady returns and the current regulatory model serves them well.”

Scott says it’s high time to clarify the ground rules. “Absolutely we need more clarity from Ofgem – but we’ve had a couple of years where they appear to have passed the microphone over to the Open Networks Project. We’re now in 2020, soon we’ll we heading into 2030. Will we get there only to find it’s a ‘DNO-plus’ world when we ought to be in a DSO world?”

At WPD, however, Turvey is in forgiving mood. “Clarity is lovely when you’re dealing with Ofgem, but there are a lot of uncertainties and Ofgem is in the same situation as others, it’s very hard to see what will happen in the next five years. More clarity would always be good, but I’m not sure you ever get enough in those processes.”

While the DNOs themselves feel confident that the transition is happening at a good pace, the DSO implementation plan from the ENA and the Open Networks Project will also give outside observers a chance to judge whether speed really has picked up enough.

Please login or Register to leave a comment.