You’ve reached your limit!

To continue enjoying Utility Week Innovate, brought to you in association with Utility Week Live or gain unlimited Utility Week site access choose the option that applies to you below:

Register to access Utility Week Innovate

- Get the latest insight on frontline business challenges

- Receive specialist sector newsletters to keep you informed

- Access our Utility Week Innovate content for free

- Join us in bringing collaborative innovation to life at Utility Week Live

DNOs regularly publish Distribution Future Energy Scenarios, but these often overlook the developing complexity on the low voltage networks. As UW Innovate reports, WPD has now devised a new methodology, called EPIC, to capture data from local authorities and use it for more sensitive and localised analysis.

Regional energy strategies are emerging from focus groups and workshops in council offices across the country, but just how well do their aspirations match up with the pipes, wires and substations on the ground?

Meanwhile, gas and electricity network operators produce technically detailed Distribution Future Energy Strategies that might reflect local authorities’ big picture thinking, but rarely capture the fine-grained detail of localised plans or low voltage networks.

To span between the two types of future-gazing, Western Power Distribution (WPD) is three months into its EPIC project, or Energy Planning Integrated with Councils.

EPIC set out a process for engagement and data sharing between the distribution network operator (DNO) and local authorities, to align the two types of approach. The idea is to produce robust projections that can lead to real cost savings – for both the councils and the network operator.

There is also a cross-vector approach, with gas network operator Wales and West Utilities (WWU) being factored in too.

“We don’t want to allocate lots of heat pumps to an area where the gas network is being changed for heat networks, or another alternative. So it’s checking our assumptions – not just between us and the local authority, but a three way process that involves the gas distribution as well,” says Jenny Woodruff, project lead and low carbon and innovation engineer at WPD.

The 20-month project, which launched in February 2021, has funding of £540,000 from WPD and WWU’s Network Innovation Allowance, and will also draw on the expertise of energy consultancy Regen, Power Systems Consultants (PSC) and EA Technology.

EPIC should also have wider resonance outside WPD’s south west patch. “We are not the only people looking at local energy planning – there is a lot of interest,” says Woodruff. “A work group of the ENA Open Networks project is looking at how best to share data to support planning activities and we are trying to work in step with what they are doing. We’ll also be giving a Cost Benefit Analysis Tool developed by Open Networks its first use in practice and hopefully that will provide useful feedback”.

Essentially, the EPIC project builds on the type of scenario planning that WPD and other DNOs already carry out annually, to create regional Distribution Future Energy Scenarios (DFES) based on the National Grid Future Energy Scenarios.

Building a picture block by block

As Woodruff explains, the DNOs first identify various “building blocks” that are set to change the regional supply and demand profiles, such as electric vehicle (EV) charge points, new housing or commercial developments, or domestic PV installations. By adding the impact from the building blocks to existing known loads, WPD can carry out power flow analysis and model the impact on the network.

This allows it to identify potential overloading of the network or areas that will be close to the voltage limits, determining whether to plan reinforcement works in specific areas or to procure flex services to resolve the issue.

But that DFES process is carried out only in relation to the 33kV networks and higher voltages; now, through the EPIC project, WPD is turning to lower voltage networks.

“We’re not starting from scratch, but the current process is limited to the 33kV and the high voltage network, where there is a need to think long term and in advance. If we’re going to do something like introduce a new primary substation, that’s a long lead time item, it’s not something you can do very, very fast. So you need to have that forward view looking several years ahead,” says Woodruff.

“We’re now saying, can we extend that process to the lower voltages, so that we’ll be able to show on a more local scale where we think the network will need to be improved.”

“And we think that having it at a more local scale will also make it easier for local authorities to engage with and relate to,” adds Christine Chapter, head of innovation at Regen. “The service area covered by one primary substation can be quite large and it can be difficult for the local authority to say ‘what does that mean?’”

For example, a council with high ambitions on transport electrification might want more EV charge points than would be normally be allowed for WPD’s pro-rata formula based on the FES; the EPIC project can now capture that aspiration and plan for it at a localised level. Other variables might include small scale renewable generation or the installation of local heat networks.

“While the FES works downwards, what we’re trying to do with EPIC is more of a bottom up approach on the lower voltages. We’ll use the DFES data as a starting point, but then we’re trying to up the engagement with local authorities and unitary authorities and show them the existing data and what that might mean for their area, and discuss their ambitions and strategies so we can update the data to better reflect local policy.

“This is adding to the existing stakeholder engagement that’s part of the DFES process to incorporate local authority ambition and strategies,” Chapter explains.

Where’s the money?

In part, the project could help to identify some of the sector’s “missing money” – in other words, the capital expenditure that is saved or retained when a network company opts to procure flexibility rather than physically reinforce the network upgrade infrastructure. While a press announcement might declare a “£5 million reinforcement saving”, often there is no way to reflect money “saved” in terms of the bottom line financial accounts.

But by looking across both WPD, WWU and the local authorities’ budgets, it’s possible that avoided costs can more clearly be identified as budget savings.

“When we’ve got a problem with a network, we tend to assess that very much in terms of what does that mean for our network – what’s the costs, or the benefit of solutions we propose? But with the EPIC project, can we take into account that benefits to other parties of the solutions that we implement?” Woodruff explains.

“If we put in a new transformer rather than buying flexibility services, is there a knock-on benefit to the local authority because the additional capacity helps them with something they’re planning, or should we actually avoid the cost because the gas network is doing something the following year? Rather than do the costs benefits separately for each party, we’ll try and take into account the impacts on each other,” she says.

The EPIC project is exploring the use of an existing software tool to achieve this. “We’re looking to give a cost benefit tool developed as part of the Open Network Project its first real-world use. It has been specifically designed to incorporate third party benefits so it should be ideal to help us put together cohesive investment plans.”

It will also adapt another piece of software: the Network Investment Forecast Tool (NIFT) from EA Technology, which will analyse the future implications for the low voltage network infrastructure of the additional loading from heat pumps or EVs.

“If you give that a whole load of data for the LV network, it will analyze the impact of those additional heat pumps and electric vehicles that are associated with particular distribution substation to see what the impacts are likely to be, so it’s like a very much more localized version of the analysis we do for the EHV networks,” says Woodruff.

Looking west

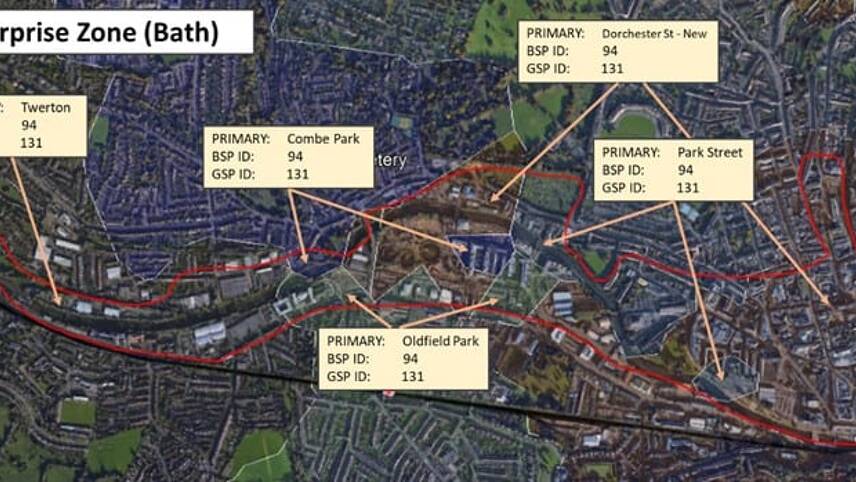

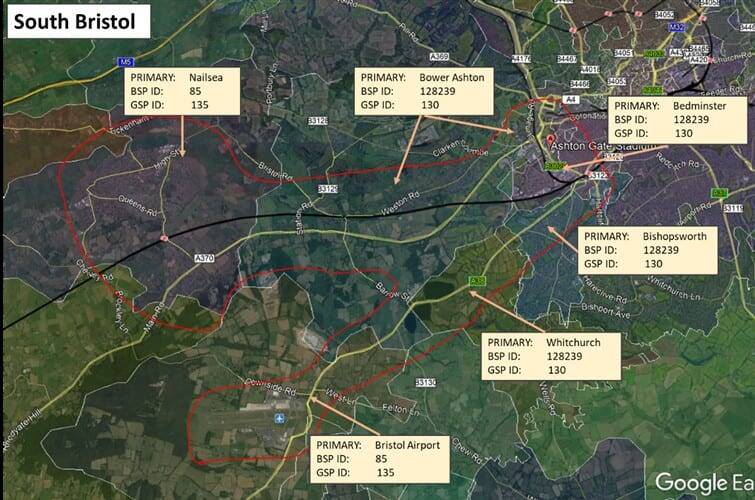

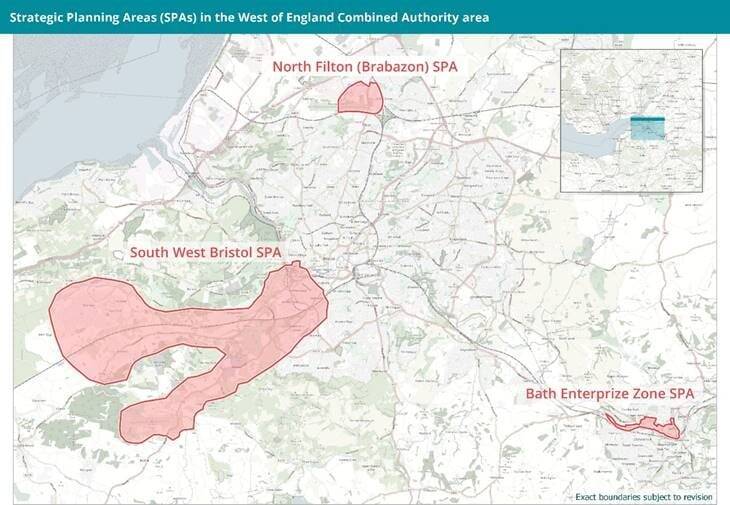

EPIC will be trialled in three areas chosen for their contrasting demand profiles: North Filton, a former industrial sites now redeveloped for housing, the business customers in the Bath Enterprise Zone and commuter belt South-west Bristol.

“Some local authorities will have dedicated energy specialists, who will have all the data at their fingertips, while others may not have the same resources and processes,” says Chapter. “Local authorities are all different and may not have the same resources and emphasis, so we’re making sure the EPIC process can be adapted to be consistent between them all – and replicable.”

The process incorporates six step including different levels of data exchanges to first create an energy plan, carry out network analysis, suggest network investment options and finally combine these to create an investment plan.

Once WPD has the drawn up the basic projection, the plan is to use it to explore different use cases and sensitivities to see the different results from different choices. Woodruff emphasises that these are tailored following feedback from local authorities or other partners.

For instance, on investment strategies, WPD will be able to compare and contrast investing the minimum required in a “just in time” strategy, versus spending more on upfront upgrades and resiliency in a “one-touch” strategy. “You might put in a much larger asset initially when you are confident the capacity will be needed in the future and this will save the cost of repeated incremental upgrades ,” she says.

Other uses cases will explore the impact of investment in improving the building stock in an areas in order to improve energy efficiency; and different options on expanding capacity using flexibility or by reinforcing an asset.

EPIC will also explore different variants for EV charging, such as a greater number of lower capacity on street chargers versus fewer high capacity rapid charging hubs, while taking into account any local authority plans, and the impact on both the gas and electricity networks of installing hybrid heat pumps in particular areas.

From niche to mainstream

At the moment, WPD prefers not to pre-judge how widely the EPIC methodology will be applied after the project. “We’re not sure if this will be a specialist approach targeted on particular areas where the local authority plans are significantly different to our strategic planning assumptions, or whether we can make this so light and easy to apply that we could make it more widespread,” says Woodruff.

“Once we’ve been able to assess the results of working collaboratively in the trial areas we’ll be able to see the added value compared to the plans we would have created working alone. We’re hoping to show the added value outweighs the costs of supporting the process.”

But in addressing the current and pressing need among DNOs to create more transparency and visibility across the low voltage networks, it does seem as if EPIC is a project whose time has come.

Please login or Register to leave a comment.