This is the Sponsored paywall logged out

Without regional water transfers, investment in new reservoirs, and demand reduction the UK will face a water supply crisis in the next 25 years. Stephen Cousins reports.

The saying has it that “it never rains but it pours”, but England’s reputation for wet spells, drizzle and April showers belies the fact that its water supply system is under stress and the impacts of climate change and population growth threaten to push it to breaking point.

The saying has it that “it never rains but it pours”, but England’s reputation for wet spells, drizzle and April showers belies the fact that its water supply system is under stress and the impacts of climate change and population growth threaten to push it to breaking point.

Over half of summers are expected to be hotter than the 2003 heatwave by 2040, resulting in more water shortages, particularly in the drier south and east, and potentially 50-80 per cent less water in some rivers in the summer.

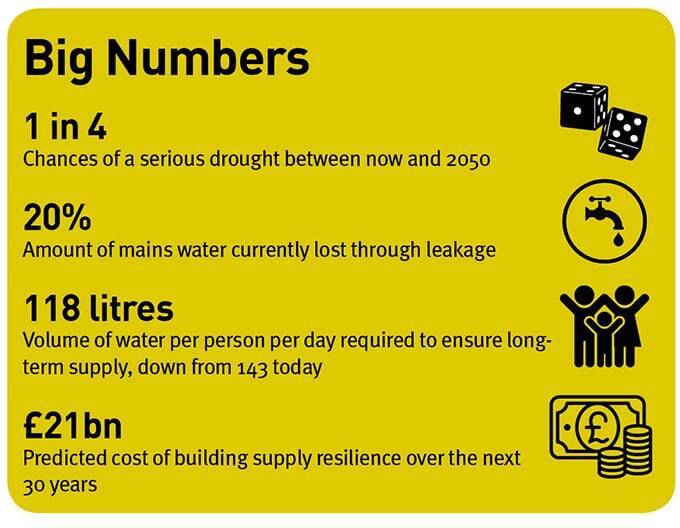

The UK population is expected to rise from 67 million to 75 million by 2050, increasing demand for water, yet currently about one-third of water is lost to leaks or wastage and few households make sufficient efforts to conserve their water use.

Environment Agency chief executive Sir James Bevan spelled out the severity of the situation in his keynote speech at the Waterwise conference in March, warning that as demand rises and supply falls and the “effects of climate change kick in” the country will enter the “jaws of death”. He suggested that England would run short of water within 25 years unless action was taken.

Bevan called for measures to cut people’s water use by one-third, and for leakage from water company pipes to be reduced by 50 per cent. He also wants new mega-reservoirs and desalination plants built, and more cross-regional water transfers.

Similar concerns are highlighted in the recent National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) report Preparing for a Drier Future, which sets out a blueprint for how government, water companies and the regulator should increase investment in supply infrastructure and encourage more efficient water use.

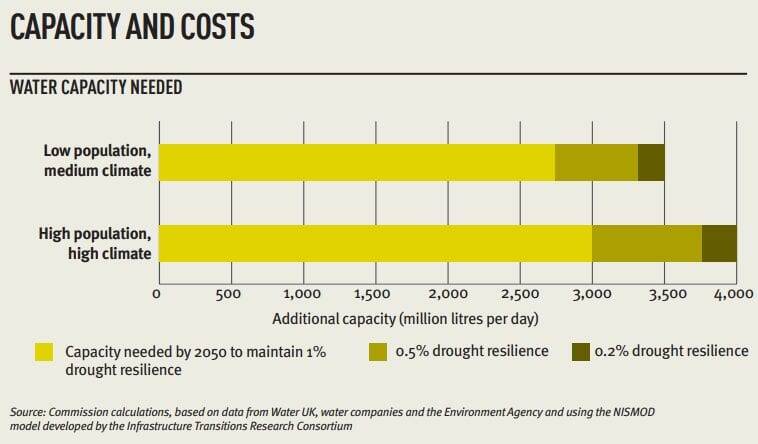

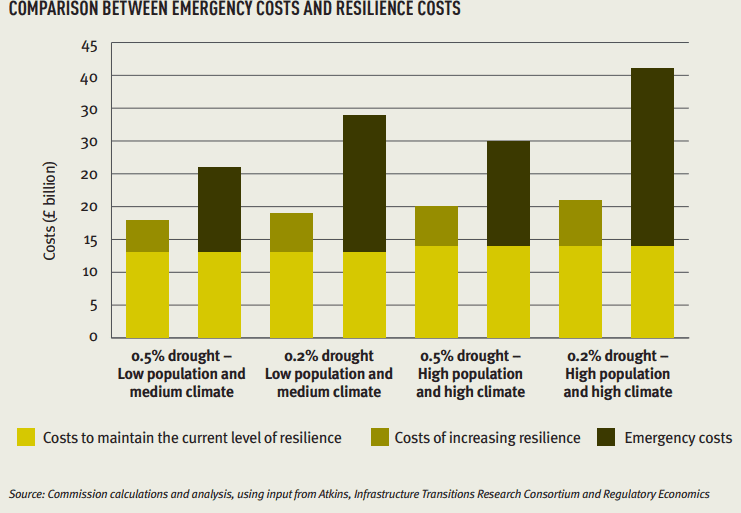

The paper estimates that the cost to the country of not taking action will be roughly double that of boosting supply resilience, and it asks government to implement plans for an additional 4,000 million litres a day (Ml/day) of supply by 2050.

Some of its recommendations have already been taken up. The government and Ofwat have adopted the long-term target of cutting leakage by 50 per cent by 2050, and this will be built into the next round of water company Water Resource Management Plans. A number of regional groups have been set up to ramp-up efforts to collaborate to support water transfers between companies and regions.

However, critics claim that much more needs to be done. Among their complaints are: that the government has yet to sign up to NIC’s 4,000Ml/day target; that water companies have a poor track record on stemming leaks; and that more needs to be done to support the long-term planning and investment needed to deliver major infrastructure projects such as reservoirs.

Trevor Bishop, organisational development director at Water Resources South East (WRSE), one of five regional groups set up to deliver more resilient water supplies, says: “The NIC has set out an incredibly bold agenda – significant reductions in leakage and per capita consumption combined with a major infrastructure programme for hard, soft and green infrastructure.

“Government, regulators, companies and other stakeholders are starting to work much more collaboratively with a common cause, but many barriers – both policy and cultural – still exist and there is much more to be done, particularly around trust and leadership.”

The new normal

Weather in the UK is becoming more extreme, severe storms and flash flooding have occurred in the North West and Lincolnshire, 2018 saw an extended summer drought, and when the mercury hit 38.7C on 25 July this year in Cambridge it was the highest temperature ever recorded.

The need to bolster resilience in the water supply runs in tandem with goals, set out in the Paris Agreement, to keep global temperature rise well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and the UK government target to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The NIC report endorses a “twin-track” approach of reducing demand and increasing supply, as the cheapest and most sustainable method of reinforcing the network. It stipulates a minimum 1,300Ml/day of additional supply infrastructure, which could include water transfers, reservoirs, re-use and desalination plants.

Philip Graham, chief executive of the NIC tells Utility Week: “We are unable to reach a firm view [of the preferred infrastructure options] until more work has been done, but the indicative view is that transfers alone are unlikely to provide a full solution to the problem. We have been encouraging water companies to think about what level of reservoir capacity might be needed alongside that, or potentially other proposals such as desalination plants, although these tend to be very expensive.”

In its latest Water Resource Management Plan, Thames Water updated proposals to build a new reservoir in Abingdon, Oxfordshire, in partnership with Affinity Water, which if approved could begin construction in 2025. Portsmouth Water is championing the construction of a new reservoir in Havant Thicket, East Hampshire, targeted for delivery in 2029.

However, building new reservoirs in the UK is notoriously difficult because of planning and legal hurdles and often fierce local opposition to schemes. Companies are familiar with planning on a 25-year horizon, but this can come into conflict with the traditional five-year regulatory investment cycle.

As part of work to develop a more responsive regulatory approach, the Environment Agency recently committed to work with Ofwat to establish the Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (Rapid). This would aim to ensure that barriers to strategic developments were identified and removed, such as the funding of shared strategic schemes.

Graham comments: “The industry is increasingly taking a long-term perspective in terms of how it plans. But the challenge is going to be making sure that the regulatory cycle takes into account the need to plan investment over the long term rather than focus on a very narrow five-year period. Ofwat is aware of that and making encouraging noises when we talk to them. But the devil is in the detail.”

Supply concerns include the need to reduce levels of water abstraction. According to Environment Agency figures, nearly 9,500 billion litres of freshwater were abstracted in 2016, 55 per cent of which was used for public water supply. The agency has warned that even current levels of abstraction are unsustainable in more than a quarter of groundwater bodies and up to one-fifth of surface waters.

UK Water Industry Research (UKWIR) is now working to create a route map for how the sector can halve freshwater abstractions in a sustainable way by 2050.

Joined-up thinking

Strategic water transfers could provide about 700Ml/day additional capacity, the NIC states in its report, but at present just 4 per cent of supplies are transferred between individual water companies.

The five regional water resources groups covering England are currently exploring new strategic schemes that may involve transfers, and by February next year each is required to submit a statement of their resource position and whether they will be a net receiver or donor of water. The groups will then work together and with regulators to develop strategic solutions.

Trevor Bishop at WRSE comments: “WRSE is starting to develop what we believe will be an international first in terms of a multi-sector water resilience plan for the South East. This approach will start to build-in wider resilience issues, consistently and collaboratively across the region.”

Water stresses are normally considered most acute in the South East but new research, by independent research think-tank the Institute for Public Policy Research predicts that resources in the North of England will become scarcer than previously thought over the next 25 years. It calls for a “pan-regional voice” for stakeholders in the water sector with water companies working together to find solutions.

To help facilitate a wider strategic operation between water companies and stakeholders such as farmers, electricity generators and environmental groups, the Environment Agency has agreed to lead development of a water resources national framework by December 2019.

Stuart Sampson, water manager at the agency, tells Utility Week: “This national framework will model future water needs and set out an assessment of national and regional water needs, including indicative needs for strategic solutions such as water transfers and new sources of supply to improve resilience to drought.”

Demand reduction

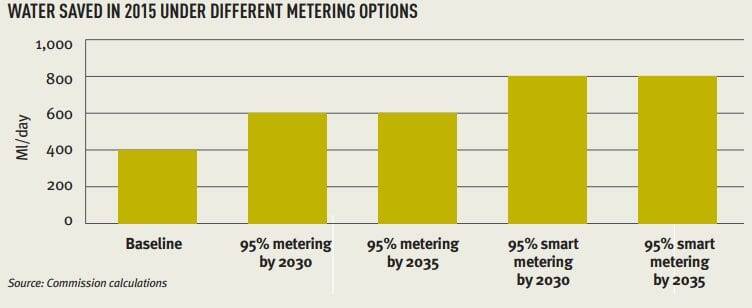

A greater focus on fixing leaks, rolling out water meters and raising awareness of water conservation with customers could deliver around two-thirds of the additional water capacity targeted by the NIC in its report.

At present, around 20 per cent of water put into the public supply is lost through leakage and Ofwat has set all water companies a target to bring down leakage by at least 15 per cent by 2025, rising to 50 per cent by 2050. However, the government has criticised the former target as “not ambitious enough” and said the longer-term goal should be reached ten years earlier, by 2040.

At present, around 20 per cent of water put into the public supply is lost through leakage and Ofwat has set all water companies a target to bring down leakage by at least 15 per cent by 2025, rising to 50 per cent by 2050. However, the government has criticised the former target as “not ambitious enough” and said the longer-term goal should be reached ten years earlier, by 2040.

The potential for leakage reduction is questionable, given that in 2017/18 almost half of companies in England and Wales missed their leakage targets. The worst offender, Thames Water, was fined £120 million by the regulator as a result.

New technology and learning lessons from other countries could help find solutions, says Steve Kaye, chief executive of UKWIR: “UKWIR has set out the goal for the sector to achieve zero leakage by 2050 in an effort to drive innovation, this will lead to greater cost efficiencies and improved operational reliability. The Netherlands has less than 5 per cent leakage and other countries have fewer losses, so so we have to ask ourselves how that is achievable.”

A significant reduction in personal water consumption could have a big role to play in future. A recent survey carried out for Utility Week by Harris Interactive found that 90 per cent of 1,022 people polled would be happy to make changes to their energy and water consumption to support the government’s net zero emissions target by 2050.

However, a third of those quizzed found it surprising that the UK had significant water shortages, which points toward the need for a high-profile public awareness exercise.

Conventional metering has been shown to reduce demand by around 15 per cent and smart meters, which provide more frequent readings, are expected to increase this to about 17 per cent.

The NIC plan recommends that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) allows companies to implement compulsory metering beyond water-stressed areas by the 2030s and amends regulations to require all companies to consider the systematic roll out of smart meters before the end of 2019.

Tom Andrewartha, director of strategy and policy at Waterwise, says: “It is only when people have an understanding of how much water they use and how they use it that we will see a step change in people’s water-using behaviour. Smart metering can help unlock that challenge.”

Further gains could be achieved if mandatory water labelling on all appliances is introduced, he adds: “Our research with water companies, Defra and the Environment Agency showed that a mandatory water label, linked to both water fittings, and building regulations, could possibly result in a PCC reduction of 31 litres per property per day by 2050. That’s one of the most cost-effective actions the government could take and something that all water companies are getting behind.”

With multiple options for building water resilience on the table, thoughts must inevitably turn to the cost of infrastructure investment and upgrades required to build resilience. All new infrastructure measures outlined in the NIC plan are expected to be delivered by water companies through the regulatory process and Water Resource Management Plans, without extra funding from government.

According to its calculations, the delivery of additional infrastructure required to build resilience by 2050 would have a reasonably small impact on consumers’ bills, costing about £10 a year by 2050.

However, the need for regional water transfer schemes may introduce additional challenges, says WRSE’s Bishop. “This relates to the allocation of costs and risks associated with schemes between companies,” he says. “It is possible that future schemes may incorporate benefits for other sectors, such as agriculture, private industry, etc. This will need to be carefully managed to ensure no inappropriate cross-subsidy between those who pay and those who receive benefit.”

Success will also hinge on support for the NIC’s plan, according to Graham, because the government has dragged its feet on measures designed to make the introduction of metering easier.

“We had hoped they would have moved faster, and the consultation [currently underway] is quite neutral,” he says. “It doesn’t say: ‘We think this should happen’. It is more like: ‘Here’s an interesting idea, tell us about it.’ We aren’t worried that this agenda is being ignored, we would just like some of the initial areas to be picked up.”

Others point to a lack of scope in the NIC’s vision of resilience.

“It does not go far enough and see the need for water services not just as infrastructure but as part of the natural water cycle,” says Nick Voulvoulis, professor of Environmental Technology at the Centre for Environmental Policy. “The water industry ultimately takes the role of guardian/manager of a sustainable water cycle. While the plan recognises the need for a more comprehensive perspective – and that companies need to work better with each other and wider stakeholders to plan for the long term – it does not propose any mechanisms or policy changes that will make this happen.”

As the clock ticks down, and global temperatures continue to rise, a concerted effort will be required to keep the water flowing in this green and pleasant land.

Cape Town narrowly averts a water crisis

The threat of turning off the taps in a dramatic “Day Zero” event helped Cape Town slash its water consumption and avoid becoming the first major city in the world to exhaust its resources.

Cape Town’s water crisis peaked in early 2018 when, following three years of anaemic rainfall, water storage levels drop to as low as 15 per cent of total dam capacity.

In January 2018 the South African government announced Day Zero, a theoretical moment in 90 days’ time when emergency rationing measures would be triggered if major dams fell below 13.5 per cent capacity. Under the provision, water supplies to suburban homes and businesses would be cut off and every resident would be forced to visit communal water collection points to retrieve a daily water ration.

The shocking prospect had a catalytic effect. Locals started taking water conservation seriously, limiting toilet flushes to once a day and recycling washing machine water. In addition to a cap on consumption of 50 litres per person per day, and hefty fines applied to non-compliant households, this galvanised a 30 per cent drop in residential consumption.

The measure formed part of a multi-pronged response to the crisis, which included the throttling back of water for agriculture and higher water tariffs for heavy users. The emergency efforts paid off and when average rainfall levels returned in mid-2018 city officials were able to push back Day Zero indefinitely.

Today, dam levels in the Western Cape Water Supply System are at an encouraging 82 percent, but the parched summer season is fast approaching.

Please login or Register to leave a comment.