This is the Sponsored paywall logged out

Economist Richard Green assesses the options for sharing out the costs of decarbonisation fairly.

Decarbonising the world’s energy supply is likely to be cheaper (eventually) than the alternative, but that doesn’t make it cheap. The 2006 Stern Review suggested a cost equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP forever; chancellor Philip Hammond has recently (and controversially) suggested a cost of £1 trillion for the UK. So who should foot the cost?

Decarbonising the world’s energy supply is likely to be cheaper (eventually) than the alternative, but that doesn’t make it cheap. The 2006 Stern Review suggested a cost equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP forever; chancellor Philip Hammond has recently (and controversially) suggested a cost of £1 trillion for the UK. So who should foot the cost?

Logically, there are three groups that could end up paying. First, individual energy consumers who want to heat their homes, power their appliances and fuel their vehicles. Second, businesses that buy energy in order to produce goods and services for sale, and public sector organisations. Third, taxpayers (who could also be divided into individuals and corporate bodies).

Decades of work by economists have given us some principles for how to pay for the government, or other projects inspired by the government. First, market prices should be as close to the true marginal cost of production as possible. The price of fossil fuels should include a carbon tax that reflects the cost of the damage done by climate change. However, estimating the value of this damage is difficult.

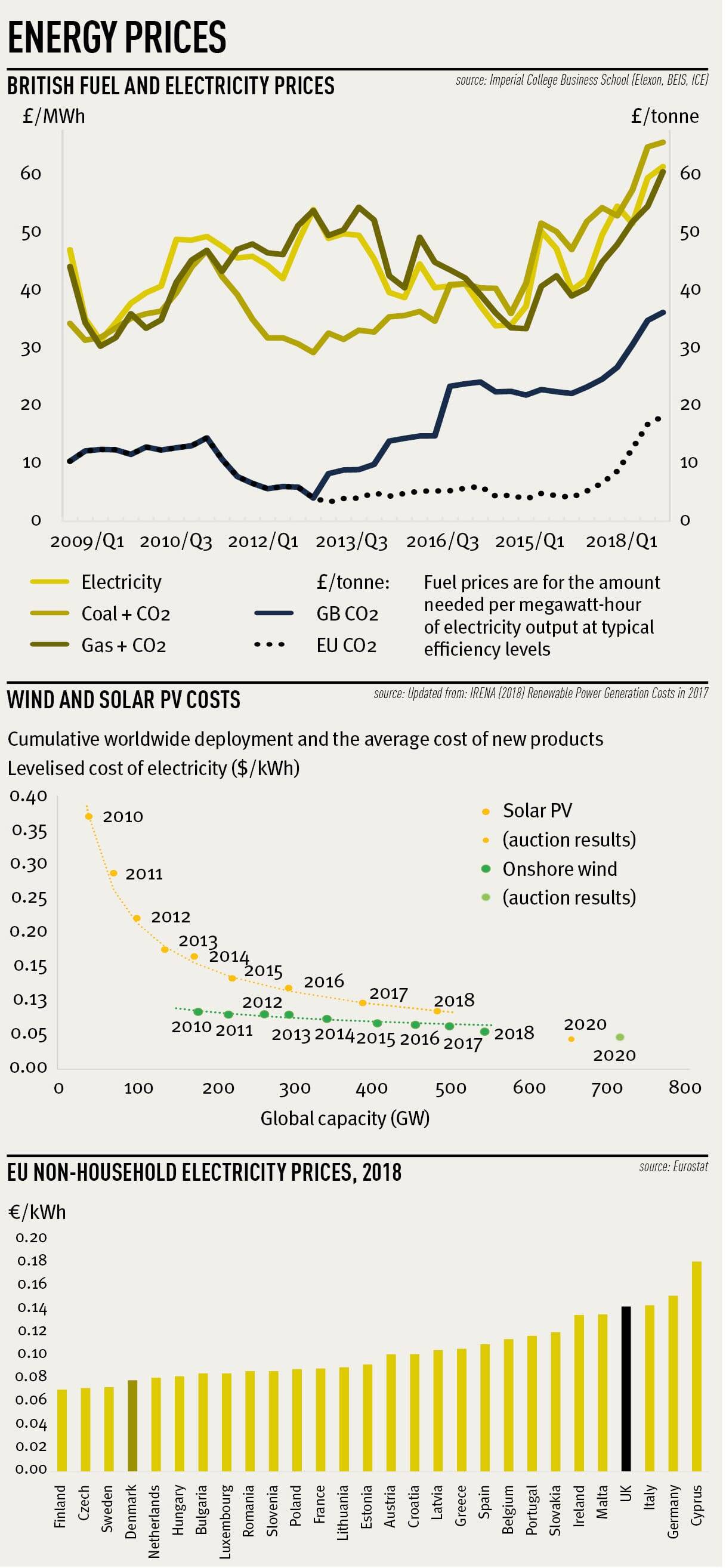

Different assumptions give different values (the previous US administration had numbers between £15 and £153/tonne of CO2 for 2020), and only time will tell whether any of these numbers are even roughly correct. We do know, however, that a carbon price of zero is precisely wrong, and the UK government now works backwards from its commitments to reduce emissions, estimating the carbon price that would spur the investments needed to meet those commitments (£14/tonne in 2020 but £81/tonne in its central case for 2030).

Carbon tax good

The good thing about adding a carbon tax to the price of fossil fuels is that it should automatically be added to the prices of the goods and services being produced with those fuels, and in proportion to the amounts used. This is most obvious in the case of electricity – the price in the wholesale market closely matches the cost of fuel, as long as the cost of carbon is included.

The good thing about adding a carbon tax to the price of fossil fuels is that it should automatically be added to the prices of the goods and services being produced with those fuels, and in proportion to the amounts used. This is most obvious in the case of electricity – the price in the wholesale market closely matches the cost of fuel, as long as the cost of carbon is included.

The chart right, “British fuel and electricity prices”, shows this relationship, and also that the rising cost of carbon in Great Britain has now made gas cheaper for generators than coal. Crowding out the dirtier production processes is exactly the point of a carbon tax, which also gives consumers a reason to buy fewer carbon-intensive products.

Carbon tax bad

The bad thing about adding a carbon tax to the price of fossil fuels is that it makes the goods produced with those fuels more expensive, and less competitive against countries without a carbon tax.

Replacing relatively clean production in the UK with imports produced while emitting more carbon dioxide would be counter-productive. International trade law allows the UK to rebate value added tax payments when products are exported, and to charge a similar tax on imports; this ensures that our exporters are not disadvantaged if VAT goes up. The equivalent would be a border carbon tax adjustment.

Exporters would receive rebates equal to the estimated carbon tax they had paid, and importers would be taxed on the difference between the tax in the UK and the tax they paid (if any) at home. It would be almost impossible to calculate these numbers precisely, but the broad-brush techniques for attributing the share of any input in the cost of a given output are well known.

With a high enough carbon tax, some lower-carbon products and processes will be competitive without further support, but this may not be enough for the deep decarbonisation we will need. In particular, transforming our infrastructure may need strategic investment in new technologies that will initially be expensive until the benefits of learning-by-doing kick in, and the early investors may not be able to capture those benefits. Such investments deserve public support, which has to be paid for.

This is the justification for the significant sums paid to renewable generators in recent decades, an investment that has now paid off in much cheaper solar panels and wind turbines.

Common sense might dictate that the cost of these and other investments (think of the early costs of carbon capture and storage) should be paid by electricity consumers, but common sense can be dangerous for your wealth. A standard principle of public finance states that taxes should not distort the cost of inputs used by firms away from their (true) marginal costs – VAT is an efficient tax design because it can be reclaimed and is only really “paid” by final consumers.

This means that while it can be appropriate for individual customers to pay electricity prices that recover the extra cost of renewable energy, prices to industrial and commercial customers should not include these costs. Countries like Denmark get this right – they have the highest household electricity prices in the EU, but their industrial and commercial prices are among the cheapest.

Danish consumers pay the costs of their (expensive) renewable support programmes, but there is no attempt to recover these from business. In contrast, UK household prices are just below the EU average, but firms pay 24 per cent more than average. Firms should pay a carbon tax, and that is likely to raise a lot of revenue that could be used for low-carbon investment, but no additional levies to support the other costs of decarbonisation.

Indeed, public finance principles don’t even suggest that the remaining cost of renewable energy should come from individual electricity consumers. We don’t expect insurance premium tax to cover the cost of treating those hurt in motor accidents – the money goes into a general pool to pay for all government spending. The costs of decarbonisation are something for the Treasury, not for Ofgem.

The principles here are efficiency – try to tax goods where demand is not too price-sensitive, so that the tax does not change people’s decisions too much – and equity – try not to levy too much tax on goods that make up a high share of low-income households’ spending. For electricity, those principles may conflict, since demand is not very price-sensitive (high tax) and it is a necessity for low-income consumers (low tax). The next chancellor will have some tough decisions to make.

Please login or Register to leave a comment.